Thursday, August 25, 2005

Aminah Robinson: An artist you just want to wrap yourself up in

AMINAH BRENDA LYNN ROBINSON

2004 Macarthur Fellow

This profile was compiled from a number of web pages and articles to give you a sense of the work of this extraordinary artist

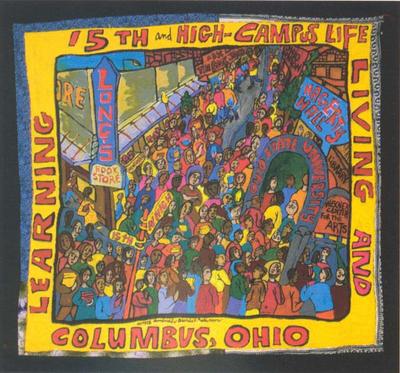

Columbus native Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson has created over 20,000 works, including cloth paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, book illustrations, and quilts. Her work is based on extensive research, oral history, and first-hand observation, but all of it is primarily concerned with documenting the lives and history of her family, friends, and community. Robinson often works for many years on a fabric piece, incorporating buttons, shells, twigs, and fabric to create richly textured works that weave a memory into a colorful and grand collage. Her work is in the collections of, among others, the Columbus Museum of Art and the Wexner Center for the Arts.

Aminah Robinson uses fabric, needlepoint, paint, ink, charcoal, clay, and found objects to create signature works on canvas and in three-dimensional construction. Folk artist, storyteller, and visual historian, Robinson celebrates and memorializes the neighborhood of her childhood – Poindexter Village in Columbus, Ohio – and her journeys to and from her home. In drawings, paintings, sculpture, puppetry, and music boxes, she reflects on themes of family and ancestry, and on the grandeur of simple objects and everyday tasks. Her works are both freestanding monuments and fractional components of an ongoing odyssey. Robinson is a master of assemblage; her elegant collages are Homeric in content, quantity, and scale (some canvases are 20 feet or larger) and many of her exhibited pieces are works-in-progress, several years in the making.

This trademark body of work resonates deeply with audiences. Symphonic Poem, for example, an exhibition of her work at the Columbus Museum of Art, was noted for its unusually large and repeat attendance.

Marion Anderson Aminah Robinson 1997 Mixed Media

Twenty-five years before the idea for the Freedom Center was hatched, Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson was already assembling the massive mural that will serve as the center's signature work of art. The 22-by-30-foot fabric assemblage, "Journeys," is the culmination of her life's work.

Aminah Robinson studied painting at the Columbus College of Art and Design. While working as an artist from her home studio throughout her life, she also worked for the Columbus Public Library and, for 19 years, ran children’s programs in the Columbus Parks and Recreation Department. Her work has been exhibited in solo and group shows at museums and galleries around the country. In addition, she has illustrated several books for children, including A School for Pompey Walker (1995), A Street Called Home (1997), and To Be a Drum (2000).

My work is about people, historical data, traditions, lost communities. For me, there is no distinction between life and art. The button work is the core. It is important because of long traditions in my family, especially from my mother. These traditions are still being passed on today, not only through me but through the younger generation. It takes time to produce work. It takes everything you have because it takes your life to leave something for those who are coming after.

Wednesday, August 24, 2005

What the f*&% is wrong with Kara Walker?

This was the question that an 18-year old brutha ran into the room and yelled at me after his virgin encounter with the work of renowned contemporary artist Kara Walker. And you know, I dig where he's coming from. Many people can't stand her and her success. In 1996 when she was awarded a Macarthur "Genius" grant at the tender age of 27 (a prize that would make a cake eater like Damon Dash slobber all over himself - its worth $500,000), African American sculptor Betye Saar sent out hundreds of letters warning that Walker's "images may be in your city next," and signing herself "an artist against negative black images." Walker repurposes the ancient southern belle pastime of silhouetting. She arranges life-size shadows in nightmarish tableaux, and scatological scenes filled with violent and transgressive miscegenation. There are no easy answers or moral truths in Kara Walker's world. This classically trained painter with an MFA from Rhode Island School of Design and a teaching position at Columbia University is a darling of the art world and a demon to many older Black artists and scholars. I've heard her described by a young Walker Art Center curator as "THE most important living American artist." At a recent Walker Art Center (no relation) artist talk, the new McGuire Theater was filled to capacity with 450 reverentially silent folk - Black and White. So, let's take a look at one of her images and see if we can discern what all the hoopla is about and what made that young brutha freak out.

Successes 1998

Here in a nearly life-size silhouette, a naked black girl kneels to suck the cock of a white slave owner. He has the claws and paws of Satan, and the jaw of an ape. His cock goes into her mouth and out her ass. And Walker gives it a devilish title as well. Exactly what are the "successes" alluded to in the title? Perhaps one of these "successes" is that the slaver has managed to get, shall we assume, his "negress" (a favorite self-referential term of the artist) to ingest and defecate his cock at the same time? I'd like to think that this seemingly powerless black slave girl who simultaneously swallows and excretes this demon is one of the "successes" referred to in the title. Maybe they've both achieved some sort of "success" and therefore the plural usage? Perhaps there is a pun in the title? What is clear is that there is more going on here than just a master/slave relationship. There are traces of tenderness in this image; touching that seems intimate and knowing. She reaches out toward his boot and he rests his paw, fingers drawn in passively, as if stroking her back with his knuckles. And what are we to imagine is in the quote box? I suspect he's making a carnal sound that is a mix of pleasure and terror - for indeed, he is trapped. If he kills her during the act of copulation what then happens to his monstrous cock? Does she clamp down and bite it off? Will he have to perform a gruesome vivisection to release his member? Is there no way to uncouple them without killing them both? Perhaps he too knows this and submits? So, what at first looks like domination is, in fact, a sinister symbiosis that is also Sisyphean in character. To me, this image might also illustrate how slavery warps the slave and the slaver alike and binds them in an eternal and infernal dance. Or, is this a scene of lovemaking?

There is a morally ambiguous (to say the least) type of interdependence portrayed in Kara Walker's work that confounds the victim/victimizer dialectic and that appears also in Consume from 1996. These psychological Moebius strips devoid of clear moral order and message are part of what I suspect drives so many people bonkers when they encounter her work. Particularly older Black artists, reared in the Black Arts Movements with its crystalline moral codes of racial uplift and Black Pride. Kara Walker just aint that clear. As Jerry Saltz wrote, "No one gets out of Kara Walker's world alive, not even the artist." And Cathy Fox, the Atlanta Journal Constitution art critic, wrote that Walker creates, "disarming, disconcerting, disturbing tableaux that explore racism, stereotypes and forbidden lusts in a way that offers no moral high ground and leaves no one-black or white-feeling comfortable." Walker says that her artistic intentions are to "make art that is self-incriminating for everybody. . . . I decided that if I'm going to delve into race and racism, as was expected of me as an African-American artist. . . I was going to pull out the stops." I'd say she'd done that and more.

There is a morally ambiguous (to say the least) type of interdependence portrayed in Kara Walker's work that confounds the victim/victimizer dialectic and that appears also in Consume from 1996. These psychological Moebius strips devoid of clear moral order and message are part of what I suspect drives so many people bonkers when they encounter her work. Particularly older Black artists, reared in the Black Arts Movements with its crystalline moral codes of racial uplift and Black Pride. Kara Walker just aint that clear. As Jerry Saltz wrote, "No one gets out of Kara Walker's world alive, not even the artist." And Cathy Fox, the Atlanta Journal Constitution art critic, wrote that Walker creates, "disarming, disconcerting, disturbing tableaux that explore racism, stereotypes and forbidden lusts in a way that offers no moral high ground and leaves no one-black or white-feeling comfortable." Walker says that her artistic intentions are to "make art that is self-incriminating for everybody. . . . I decided that if I'm going to delve into race and racism, as was expected of me as an African-American artist. . . I was going to pull out the stops." I'd say she'd done that and more.Extraordinary Resilience and Quiet Heroism: The Photography of Jan Banning

Dulrahman, nicknamed Sidul

Born 5 March, 1920, in the village of Tahunan in the Gunung Kidul region near Yogyakarta, Java. He was a romusha in various locations, finally on the Burma Railway. He is a farmer with just over an acre of land on which he raises corn, cassava, rice and peanuts. He also has some coconut trees and teak for fences and firewood.

We know from the war in Irag that photography can capture the horrors of armed conflict. But photojournalist can also find and portray stories of resilience and survival. This is just what photojournalist Jan Banning does as he listens to and portrays Dutch and Indonesian prisoners-of-war forced into slave labour and denied even minimal rights by their Japanese captors during the brutal Pacific war of 1941-45. Check out Open Democracy for three of these moving portraits from Banning's prize-winning book Traces of War due out soon by Trolley, Ltd. There is also a gallery show currently on view in London at the Trolley Gallery. So, if you're in the UK check out the work of this quietly heroic photographer.

Thursday, August 18, 2005

Finding Black Art Everywhere: The Diasporic Curator

Samuel Fosso, (Zentral-Afrika) Le Chef, 2003.

The great cathedral of contemporary art, the Tate Modern, has brought together four of the hardest working Black people in the global art scene. Chaired by David A Bailey. Three Perspectives: Curating in the Black Diaspora, was a discussion in June 2005 that brought together three curators who have made massive contributions to changing the ways that the art of the black diaspora is seen and shown: Hamza Walker, Director of Education since 1994 at The University of Chicago's The Renaissance Society; Thelma Golden with her landmark show Black Male and work at the Studio Museum In Harlem; Simon Njami with the establishment of the publishing institution Revue Noire, and recently with Africa Remix. They discuss the history of recent exhibition and the issues faced by the diasporic curator today. Get ready to have your dome rocked with knowledge, because this is five hours of a historic black art geek-out. Thanks Tate.